Istat has once again published its most recent data on employment and unemployment, and it is once again very positive numbers as far as employment trends in Italy are concerned. For months now, at least since the beginning of the year, the National Institute of Statistics has been recording a very comforting trend that consolidates and improves with each quarterly report, and the latest findings, the subject of this article, have been no exception. ISTAT tells us that in the second quarter, the employed increased by 124,000 units (+0.5%) compared to the previous quarter, with the growth of permanent employees (+0.9%) and the self-employed (+0.7%), and the decline of fixed-term employees (-1.9%). The overall employment rate reached 62.2 per cent, (+0.2 points), while the unemployment rate dropped to 6.8 per cent, its lowest level since the third quarter of 2008 when it stood at 6.7 per cent. On an annual basis, employment grew by 1.4 per cent, with 329,000 more people employed and an increase in stable employees of 3.3 per cent, accompanied by an increase in the self-employed of 0.6 per cent and a substantial drop in fixed-term contracts, (-6.7 per cent).

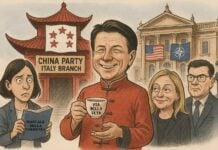

There is a marked growth in employment in central Italy, in the south and among women. Evidently, the incentives, above all in the form of tax relief and quite different from the bonuses of grillina memory, (a sprinkling of public money to then get nothing), launched by the Meloni government to stimulate hiring in the most disadvantaged areas of the nation are bearing fruit. But the increase in employment, particularly in the centre-south, inflicts a resounding lesson on the oppositions, who, contesting the reform of differentiated Autonomy a priori, tell of a phantom centre-right intent on favouring only the richest regions of Italy. Other numbers provided by Istat’s quarterly report also dispel the false myths waved by the PD and companions. Italy has long been a country, so to speak, difficult for free enterprise, but the progressive increase in self-employed workers underlines how this nation, thanks to the measures of the Meloni government, is becoming a place where people are less afraid to start something on their own, although, we are aware, there is still a lot to be done. Fixed-term contracts are falling, both quarter-on-quarter and year-on-year, and in this respect, the right-wing government differs not a little from the left because it fights and eliminates precariousness with political and surgical action, and not just in words and at rallies.

At Palazzo Chigi, people don’t talk all the time, but they work and the results come, while those who oppose the occupants of the control room, in addition to barroom chatter and ideological barricades, lose themselves in chasing the friend or ex-friend of a former minister, unleashing their sodalists in the media, attributing excessive importance to those who have none and never had any, and deluding themselves into believing that they are creating enormous problems for the government. The Right works, the Left, bereft of arguments, tries to make its way with painful and squalid gossip.